Climate change is a massive topic, so I feel inclined to frame the conversation a bit. When talking about a globe- and epoch-spanning issue, there are things we can affect, and things we can't. Most conversations around climate change are specifically about this: what, if anything, can be done, and by whom?

On the last day of the world

I would want to plant a tree

We don't have time to conclusively answer these questions today, but I can tell you where I'm coming from.

Personal responsibility and climate change

Have you been doomscrolling Opens in a new window for the last few years? You may have missed some important developments.

You have more reason to be hopeful than you might think.

The first decade of the 20th century didn't bode well for our future, and a lot of very thoughtful people easily imagined a near future without people in it.

Thanks to a lot of hard work from a lot of people all over the world, the future we're looking at now isn't apocalyptic. It's not exactly awesome, but it's something.

I won't go into all the reasons why, since that was so wonderfully covered in this video from the great folks at Kurzgesagt Opens in a new window:

Opens in a new window

Opens in a new window

Suffice it to say that if you've ever wanted to live in a time where your actions could potentially improve the lives of people for generations to come, now is the perfect time.

Lifestyle activism is pretty much a scam.

In case you weren't aware, the idea of the "Personal Carbon Footprint" is Big Oil propaganda Opens in a new window meant to shift the blame off super-polluting corporations and on to you and me.

Now of course there are things we can do in our own lives that will reduce the amount of carbon emitted by people - mostly avoiding flying, driving, and eating meat Opens in a new window.

But the biggest impact we can have is to make systemic changes, using collective Opens in a new window, economic Opens in a new window, political Opens in a new window, and legal Opens in a new window actions.

So we can say that what we do matters, and that systemic changes have an exponentially bigger return on effort. Now let's apply that to the web!

Let's look at the total carbon footprint of the web, the biggest contributors to the web's carbon emissions, and then how we can impact them.

Just how much carbon are we talking?

I've actually found that this is a hard number to pin down. Here's what I can tell you:

In 2018, Mozilla reported that internet data centres alone produced roughly the same carbon emissions as the airline industry Opens in a new window - about 2% of total emissions.

This number doesn't factor in all the other devices that form the client end of the web - phones, laptops, personal computers, TVs, watches, water pitchers Opens in a new window, litter boxes Opens in a new window, hairbrushes Opens in a new window, et al.

At the beginning of 2019, French "post-carbon economy think tank" The Shift Project estimated the total share of global emissions created by the internet to be 3.7% Opens in a new window of the 36.1 billion metric tons Opens in a new window emitted globally, (for a total of about 1.3 billion tons), but that number still doesn't capture the seismic changes in the world over the past three years.

Carbon emissions dipped in 2020, only to rebound in 2021, while work-from-home, streaming and "web3 Opens in a new window" technologies made major changes to the internet's energy consumption. But by how much?

To answer those questions, let's look at some of the big movers in bandwidth over the past two years.

The newest factors in the internet's carbon emissions

Streaming video

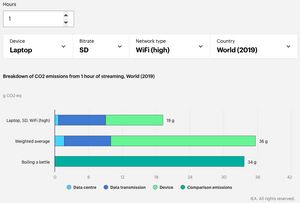

Actually some good news here: I had assumed that streaming media would be really gnarly for the environment, having read some scary articles a few years back. Turns out, watching one hour of Netflix on a big TV in 4K Opens in a new window has the same carbon footprint as boiling a kettle twice. Not too bad! And those numbers can be improved drastically by using a smaller device, and streaming in lower quality.

In part, this is thanks to the impressive efficiency gains in data centres Opens in a new window that have been happening for the last decade.

Remote work

Remote work is still, as of this writing, the subject of a lot of unsettled questions.

Remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic.

While 2020 was a great year for carbon emission reduction Opens in a new window, with a global reduction of 1.86 gigatonnes from 2019, we bounced back in 2021 in the worst possible way.

I heard murmurs that this was because so many of us were working from home, but that might not be the case.

Throughout the 20th, and into the 21st century, CO2 emissions were strongly correlated with GDP.

One of the promising indicators for, you know, human survival is that we are making progress in decoupling those numbers:

However, the rebound in carbon emissions from 2019 to 2020 suggests that CO2 emissions are less about where people work, and more about whether they work.

That said, where are people going to be working in the years to come?

In America, the vast majority of people who worked remotely due to COVID-19 are back in the workplace Opens in a new window. In Canada, "only one half (50%) of Canadians currently working from home envision themselves returning to the office with any regularity in 2022", according to an Ipsos poll Opens in a new window.

So what does that mean for carbon emissions? While the future of remote work is uncertain, we can definitely say the that working from home is (according to a meta-analysis published in the journal Environmental Research Letters) kinda good, maybe, sometimes, for the most part Opens in a new window.

Turns out that, while reducing commuting is good for the planet, those gains can be partially (or even wholly) offset by other secondary effects like buying new, rare earth element intensive Opens in a new window home office equipment and home energy use, and an increase in non-work-related travel. The benefits of reduced commutes are smallest in places where there's good public transit, where the reduced ridership Opens in a new window can negatively impact Opens in a new window lower-emission transportation.

In short, this is a hard topic upon which to draw any firm conclusions, particularly, the authors of the meta-analysis note, as work itself becomes harder to pin down. The shift to the "gig economy", contract work, and the expectation in the modern workplace of 24/7 availability - a deliberate blurring of the lines between working and doing literally anything else - makes it hard to determine when someone's carbon emissions are work-related.

To summarize: it's a very good thing when people don't drive to work, but those benefits are only as good as the sustainability of our home office equipment, public transit and electrical grid.

Web3: Blockchain, Crypto and NFTs

Finally, a true villain.

"Web3" Opens in a new window is a somewhat vague buzzword for blockchain-based… stuff. Blockchain is a technology that allows for the decentralized verification of ownership and transaction histories Opens in a new window. In other words, everybody gets a copy of a document that shows who owns what and where they got it. This is the technology that underlies most cryptocurrencies ("crypto") and non-fungible tokens ("NFTs"). While web3 is hazy and a bit speculative at the moment, we do have some understanding of NFTs and crypto.

Crypto's environmental footprint

Full disclosure: I may not know what I'm talking about here. This is a complex topic, so please understand that this is an amateur's best effort at understanding some complicated stuff, and take my words with a grain of salt. I promise I'll update this section if I understand this better in the future.

Okay, so, best as I can tell - the integrity of a cryptocurrency's blockchain relies on a process called "Proof of Work", wherein there is a bit of a lottery. The reward is crypto, but you get more lottery tickets based on how much computational power you expend. Do I fully understand how maxing GPUs, solving arbitrary, progressively harder Opens in a new window computational problems for Bitcoin, somehow verifies transactions Opens in a new window (or prevents spam email Opens in a new window for that matter)? Nope. However, the expenditure of computational resources results in the verification of transactions (somehow), and miners receive a fee for transactions they verify (I'm reasonably certain).

What I do know is that running a competition to see who can push the most computers harder and harder over time has not been great for carbon emissions.

Researchers estimate that Bitcoin mining (not including all other cryptocurrencies) in 2021 alone was responsible for about 65.4 million tonnes of CO2 emissions Opens in a new window - roughly the same as the entire country of Austria Opens in a new window. (However, let's keep it in context - 65.4 million is still only 4.9% of 1.3 billion.)

Another verification method, called Proof of Stake ("PoS"), basically requires you to put up crypto you already own as collateral for the accuracy of your version of the verification ledger. Proof of stake is less energy intensive, but hasn't been widely adopted among cryptocurrencies (although Ethereum, the next largest cryptocurrency behind Bitcoin, is planning to switch over to PoS Opens in a new window).

Ethereum is an important part of the NFT market. The Ethereum blockchain enabled "smart contracts" in 2017, which lead to the NFT market of today. These smart contracts aren't necessarily contracts in the traditional sense, but the execution of a computer function on the blockchain itself, meaning that you can trade something more complex than a "coin" (a coin being, in essence, a series of alphanumeric characters).

This opened the door to trading non-fungible tokens. NFTs are digital goods, which… well, they're also a series of alphanumeric characters, but when an NFT is traded, you're executing a smart contract where the digital signature of the file Opens in a new window (rather than the entirety of the code) is authenticated. I'm pretty sure.

How much carbon does Ethereum currently produce? Probably about 7.9 million tonnes per year Opens in a new window - a fraction of Bitcoin's carbon footprint, but a lot more than nothing (and, hopefully, about 1000 times as much as it will produce after the long-awaited Opens in a new window switch to Proof-of-Stake).

What percentage of that is due to NFTs? This is not something I could find a lot of sources on. ARTnews cites estimates ranging from 1%-2.5% Opens in a new window of Ethereum transactions being NFT exchanges (the vast majority of the remaining percentage being trades of Ethereum's native cryptocurrency, Ether, a.k.a. ETH).

But here's where we draw what some people claim as an important distinction - mining vs. transactions. Mining, i.e. the computationally expensive proof-of-work, is the #1 source of crypto's carbon emissions by orders of magnitude. The transactions themselves create a fairly negligible amount of emissions. The mining creates the capacity for the transactions, and the number of transactions doesn't directly affect the size of crypto's carbon footprint.

That being said, the transactions result in fees paid to the miners, who are incentivised to build out the capacity of the network through Proof of Work. Essentially, this capacity is what results in the massive carbon footprint of blockchain technologies. The reason it's tough to come up with a number to represent the carbon emissions per NFT is that the carbon emissions will still happen without the transactions, but the reason for the carbon emissions is because the transactions incentivise the capacity building.

If you’re on the plane, you’re obviously responsible for a portion of its emissions. But if you hadn’t bought the ticket, the plane probably would have taken off with other passengers and polluted the same amount anyway… If enough people decide to start flying who weren’t planning to before, an airline might decide to operate more flights — which means more emissions overall.

So where is this headed? Ugh, who knows. A significant chunk of the NFT market moved from Ethereum to proof-of-stake driven competitor Solana Opens in a new window at the beginning of the year, but then Solana has had a bunch of outages this year Opens in a new window, and maybe Ethereum will finally switch to PoS and reduce their energy consumption by 99.99%, as claimed by Danny Ryan Opens in a new window, a researcher for the Ethereum Foundation. Unfortunately, there are no such plans for Bitcoin Opens in a new window, and who knows what the plan is for the cash being "shoveled" at Web3 companies Opens in a new window by venture capital firms.

What can we do about it?

Okay, to recap:

- There's good reasons to not give up on the good ol' planet earth.

- It's good to make some personal changes, but some choices matter way more than others.

- It's most important to push for systemic changes.

- Watching TV is okay, or making tea is not, depending on how you look at it.

- Working from home won't save the world.

- Improving energy efficiency of big consumers (like internet data centres) has a massive impact on carbon emissions.

- Bitcoin is really, really bad for the environment, and probably won't get better any time soon. But it still only accounts for less than 5% of the internet's total carbon emissions.

- NFTs aren't great, but they're a tiny fraction of the crypto world, and are likely to be less energy intensive in the near future.

- "Web3" is vague and kinda sketchy.

So what do we do with this?

Well, I'm not going to make any grand pronouncements, but I will recommend a book: The Wizard and the Prophet Opens in a new window by Charles C. Mann.

In it, he contrasts two environmental philosophers from the early- to mid-20th century, William Vogt and Norman Borlaug. Vogt was a radical conservationist, Borlaug an optimistic technologist. Mann doesn't offer any firm conclusions about who was correct - they were both right in some very important ways, and wrong in others. My takeaway is that you can't discount either perspective, as climate change needs to be addressed in a lot of ways all at once - some of which mean reducing our consumption (of fossil fuels, or meat, for example), and some that mean creating new capacities (for carbon sequestration and renewable resources, to name two examples).

Overall, I love this list of ranked solutions Opens in a new window from Project Drawdown.

Get to the part about more sustainable internet already!

Okay, yeesh. Let's talk about systemic changes that we can advocate for:

Changing the system

The most powerful tools we have in our toolbox are not hoping that corporations will be nice to us Opens in a new window, but publicly accountable regulatory bodies Opens in a new window and trade unions Opens in a new window. Regulation needs to be done with an eye to secondary effects (for example, research published in the Joule journal suggests that China's ban on PoW Bitcoin mining perversely lead miners to turn to energy from less renewable resources Opens in a new window).

The internet's carbon emissions are, for the most part, no different from carbon emissions produced by any other energy-hungry industry, and can reduced the same way - providing the industrialists with the "carrot" of cheap green energy technology Opens in a new window (which gets cheaper the more we invest in it), and the "stick" of carbon taxes Opens in a new window.

Of course, we can hope that the big tech players stick to their pledges Opens in a new window, but, as usual, trust 'em Opens in a new window as far as you can throw 'em Opens in a new window.

If you're in a litigious mood (and who isn't from time to time?), you can sue a polluter Opens in a new window! The Paris Agreement is often the subject of people's disappointment, but it has been the foundation of numerous lawsuits by citizens suing their governments in countries like the U.K., Turkey and France, and in 2021, the case of Milieudefensie et al v Royal Dutch Shell was heard at the Hague, where they handed down a landmark ruling in environmental law - the first major ruling Opens in a new window against a corporation.

Changing a website

Are you working on the web? The more popular the website, the bigger an impact you could have!

To level-set, the Website Carbon Calculator Opens in a new window gives us the following info:

The average web page tested produces approximately 0.5 grams CO2 per page view. For a website with 10,000 monthly page views, that's 60 kg CO2 per year.

This number is based on the "page weight" of the page visited.

What is "page weight"?

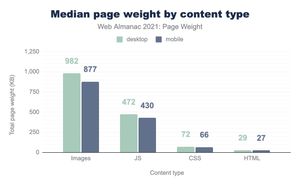

Whenever you visit a page on the internet, you're asking for a remote computer (a "server") to send you all the files you need to see the page - an HTML file, and probably a bunch of images, and files containing the CSS and JavaScript code to style the page and provide interactions. The size of all those files combined is the "weight" of the page you're visiting.

I've had the opportunity to work on the homepages of some major corporations, and shaving just a small fraction of the page weight from a page that gets millions (or billions Opens in a new window) of monthly visitors could save thousands of kilograms of emissions every year!

How do you reduce page weight?

That's a topic that I'm going to devote a whole lot of attention to on a separate occasion, but I can tell you this: the low-hanging fruit is always images. Use less images, and use images in a smarter way (with compression and modern image formats). Images are almost always the biggest part of a page's weight.

The average page weight is now 2.2MB Opens in a new window.

Here is the entire text of Charles Dickens' Great Expectations Opens in a new window. At 1MB, it's less than half the size!

Another recommendation I'll make, if you're working on a website for someone else: tell them it will make them a bunch of money.

Seriously, the lower the page weight, the faster your pages load, and the faster your pages load, the more money you make. Don't take my word for it:

via instant.page Opens in a new window

- Amazon (PowerPoint, slide #15) Opens in a new window: 100 ms of latency resulted in 1% less sales.

- Google (video) Opens in a new window: 500 ms caused a 20% drop in traffic.

- Walmart (slide #46) Opens in a new window: a 100 ms improvement brought up to 1% incremental revenue.

- Mozilla Opens in a new window: Shaving 2.2 seconds off page load time increased downloads by 15.4%.

- Yahoo: Opens in a new window 400 ms resulted in a 5 to 9% drop in traffic.

Understanding the carbon footprint of a website

You can get an estimate of any website's carbon emissions from the Website Carbon Calculator Opens in a new window.

I did! Here's the result for this page (even with a bunch of pictures and graphs and a painfully long description of how NFTs use smart contracts on a proof-of-work blockchain):

If it's your website, you can always improve it - the Website Carbon Calculator recommends three actions:

If it's someone else's website, especially if it's somebody like your college or employer, tell them you want them to do better!

A solar-powered website

I'm going to end today with one of my favourite things on the internet: a website that runs entirely off solar energy.

Rather than running off a green hosting service, they deliver their website to the entire world using a single tiny computer Opens in a new window powered by a 20 watt solar panel connected to a small battery. The background of the website actually shows the battery level! When the battery is drained entirely, the website will go offline - but it's up 95% of the time (a little more in summer, a little less in winter Opens in a new window).

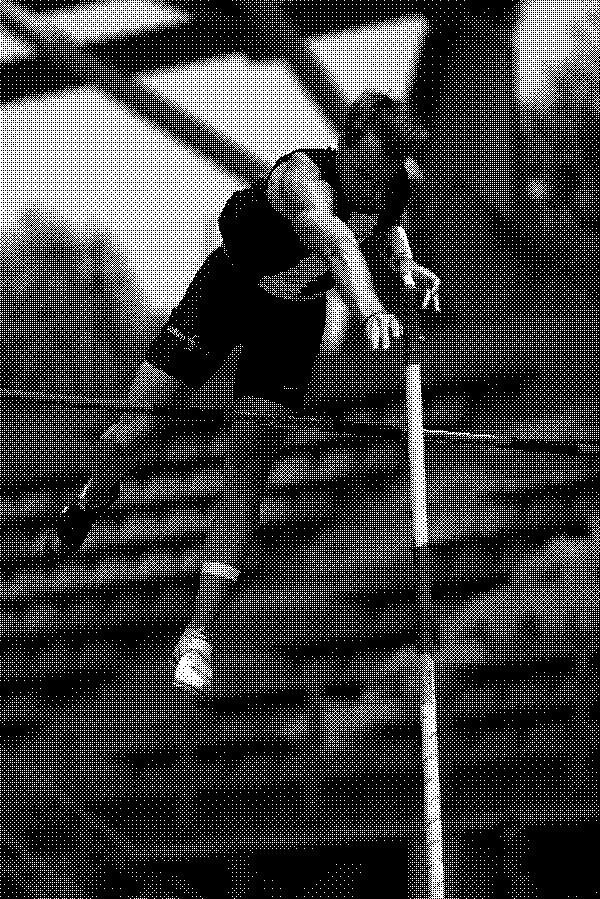

This is made possible in part by keeping their average page weight low - they report an average of 0.5MB per page - by delivering their pages without a database, without custom fonts, and using an old-timey image compression technique called 'dithering'.

Full disclosure, when I initially dithered this image using the ImageMagick CLI Opens in a new window on my computer, the file-size, counter-interuitively, got about five times bigger. Turns out dithering only reduces file sizes in a "lossless" compression image format (like PNG, as opposed to a lossy format like JPEG). But I still can't get the dithered file size smaller than the full-colour, full-resolution versions I generate in modern web image formats AVIF and WebP Opens in a new window. I have so much left to learn about compression!

To be perfectly honest, I actually prefer the aesthetics of their bare-bones solar-powered website to their regular website Opens in a new window - it feels like I'm reading off a calming e-ink screen (which are, themselves, extremely energy efficient! Opens in a new window).

Is it practical for everyone to run their websites off tiny, solar-powered computers in Barcelona? I wish! But it's a great example of the convergence of many small solutions that can reduce the web's carbon emissions.

Too long, didn't read

- Now is not the time to give up hope for the climate. Instead, it's actually the best time to work for a greener future.

- Our actions should be chosen based on their impact, prioritizing systemic change - this is true in our daily lives, and on our websites.

- The carbon footprint of the internet is about 3.7% of humanity's total yearly CO2 output - in the neighbourhood of 1.3 billion metric tons.

- This footprint includes energy sources for our personal devices (phones, smart TVs, etc.), the data centres that power the web, and the resources that go into manufacturing hardware.

- Better technological efficiency is helping, but the internet just keeps growing.

- Streaming video isn't that bad for the environment.

- Working from home is probably good for the environment, but it's a tough thing to measure, and even harder to make generalizations about.

- Bitcoin is just bad for the environment - it's about 5% of the total emissions for the whole internet, and will only get worse.

- NFTs don't have a huge impact on the whole, and may be getting better (when the Ethereum blockchain improves).

- Corporations won't fix things on their own.

- Governments can help, but may be slow, or make missteps.

- Some major changes are starting to happen through the courts when people sue for climate justice.

- Better websites mean less emissions.

- Websites get greener when they're smaller, and the biggest factor is image compression.

- You can run a nice-looking website off a single solar panel in southern Europe!